Filipino Mustangs

The Philippine's first "air force" appeared in 1940, when the 6th Pursuit Squadron of the Philippine Army Air Corps (PAAC) received 2 Boeing P-12E, augmented in 1941 by a dozen P-26A Peashooters. This was all the air defense available when the Japanese invaded. The few pilots fought courageously against the superior Japanese air force, but soon were totally defeated. Most of the pilots then joined the guerrilla units. The rest became POWs to the Japanese, many dying in captivity. US forces had informed the guerrilla fighters to prepare to transfer their pilots as early as 1943, but the first transfer only took place in August 1944.

Birth of the Philippine Air Force

|

| Philippine AF insignia. |

Over the next few months, increasing numbers of pilots were taken to the USA for refresher training. Rumour had it that the Filipino pilots were to be part of a P-47 Thunderbolt unit, as most pilots who completed their refresher training were then trained or P-47s or P-51s. In the meantime, the Philippine forces were re-established as General MacArthur liberated. The first PAAC squadrons to be activated were maintenance, supply and headquarter units. On September 1, 1945, the 1st Troop Carrier Squadron was created and began operations during the autumn. Training slowed down with the end of the war, and pilots did not return to the Philippines in large numbers until early 1946. At the time, only the few C-47s and L-5s from the 1st Troop Carrier Squadron were available, so many pilots were dispatched to civilian airlines temporarily.

At this time, the Philippines still belonged to the USA, although independance was scheduled for July 4, 1946. US authorities were none too enthusiastic about a Philippine Air Force and reluctant to supply aircraft and equipment. However the Truman doctrine of March 1946 mentioned the Philippines as receivers of the military aid, and new units were created in anticipation of the new material.

These units included the 1st Fighter Squadron, activated on May 1, 1946. The unit's commanding officer was to be Capt. Godofredo Juliano, one of the few prewar PAAC pilots, who had survived two dogfights with Japanese A6M Zero fighters. The squadron was established at Lipa Air Base, and was soon joined by the 1st Liaison Squadron. Both were placed under the Composite Group led by Maj. Pelagio Cruz.

There is quite a bit of confusion on the transfer of P-51s from the USA to the Philippines. Some sources claim deliveries started immediately after independence, while others say the Mustangs were held in the USA for more than a year, even though they officially belonged to the PAAC. Anyhow, very little flying was done in 1946 and early 1947. Pilots sometimes managed to borrow an L-5 from the neighbouring 1st Liaison Squadron, or participate in their training programs, but the lack of activity and very low salaries led to several pilots leaving for jobs in civilian airlines.

On November 25, 1947, the 2nd Fighter Squadron was created but oddly remained a "phantom" unit, not even being appointed a commanding officer. The PAAC was re-designated Philippine Air Force (PAF) on July 3, 1947, and was made officially a separate branch of the armed forces on October 24.

|

| A flight of 7th Fighter Squadron P-51s. The lead ship is nicknamed "Tayo Na". |

The new and expanding PAF needed additional airbases. One of the sites that had been considered was a small airstrip near Floridablanca in the Pampanga province. Originally built by the USAAC prior to World War II, it had been improved first by Japanese occupation troops and then by the USAAF in 1945 as a bomber base. A small group of PAF officers and men started preparing the base in August 1947. As soon as basic facilities were installed, the fighter units started moving in.

Meanwhile, PAF air units where being re-designated, as there were at least six '1st' squadrons, and a lot of confusion. In October, the 6th and 7th Fighter Squadrons were created. The number '6' was chosen to commemorate the prewar 6th Pursuit Squadron. The 6th FS was commanded by 1st Lt. Lucio S. Java, and the 7th FS by Capt. Fidel T. Reyes. Both were veterans, having graduated in 1941 with PAAC, and completed training in the USA. To complete the re-organization, the 5th Fighter Group was created and commanded by Maj. Benito N. Ebuen, ex-commander of the PAAC's 7th School Squadron of 1941.

It is probably at that time that the first Mustangs arrived, although sources do not always agree to this. USAF records state that at leat 31 P-51Ds were transferred in August and September 1947. Philippine sources claim only 18 fighters were available at the time, the rest possibly being held in store at Clark in the USA.

Nevertheless, with no more than a dozen pilots available, 18 P-51s were enough. In addition, the group operated a C-47 and several L-5s. On April 20, 1948, the Floridablance AB was renamed Basa AB after Lt. Cesar Basa, a PAAC P-26 pilot killed in 1941. Conditions at Basa AB were rather primitive, and although new facilities were progressively being installed, the area was a semi-desert in the summer season, dust and heat making life hard for those based there. In addition, the base was rather isolated, which luckily limited interference from headquarters. Indeed, in these early days, Wing headquarters imposed a weekly flight schedule, but pilots were allowed to fly more if they wanted to. Some attempts to instore a training program were made halfheartedly by US instructors, none of which permanently based at Basa AB.

Maintenance was sparse to say the least. No hangars or workshops were available, and spare parts were rare, thus leading to the cannibalisation of several aircraft. Canopies cracked from the intense heat or become opaque and tyres were in short supply. Operational readiness was in the 25% range, which was considered relatively good given the conditions. [Nowadays, squadrons boast readiness records which are often over 90%, but one should keep in mind that today's technicians are better trained, and maintenance has become something of an art. After World War II, maintenance pretty much meant repairing what was broken. Nowadays, maintenance means anticipating breakdowns.] Only minor repairs were done, and any serious damage usually meant the aircraft would be written off. This was not such a problem, as lots of aircraft were available, and the ones that had been written off could still be used for parts.

Safety was also a secondary concern. No fire fighting equip;ent was available, and the base had no security force, and wasn't even fenced in. This is why Lt. Felix Pestana wrote off a Mustang by landing into a herd of carabao (a type of buffalo) which had wandered onto the runway. The pilot was only slightly injured, but the animals and the aircraft took somewhat more damage.

In addition, accidents were very frequent, especially with younger inexperienced pilots, who often crashed after trying to impress relatives or girlfriends with low-level aerobatics or other features of the sort.

The Huk campaign

The 5th Fighter Group quickly got involved in the operations against the Huks. Originally a peasant protest movement in the 1930s, the Hukbong Mapagpalayang Bayan (People's Liberation Army, or Huk for short) fought a very effective guerrilla war against the Japanese and then turned against the government in 1946. The first missions the PAF flew against the Huks were rather uncommon: L-4s were send on bombing missions, throwing hand grenades on the ground troops. The Mustangs first intervened by patrolling the coast for boats delivering weapons to the Huks, although none was ever found.

Even more surprising was the fact that Basa AB was well within the Huks' territory, with no proper security force or army unit to protect it. The Huks originally had no grievance against the air units and did not attack the base, and, early in the conflict, armed bands asked for - and were granted - the permission to cross the airfield to and from operations.

This most unusual situation did not last however, and starting in the autumn of 1948, Mustangs started being used for strikes against Huk hideouts. In 1949, the fighting was spread to several other provinces, and a flight of Mustangs was temporarily based at Fernando AB to assist local operations.

In the same year, air operations started against the Muslim rebels on the island of Mindanao, led by Tawan-Tawan. Flights of the 6th FS and 7th FS were based at the civilian airport in Zamboanga from where they flew army support missions until Tawan-Tawan was defeated.

The first Filipino pilots

In May 1949, the first batch of Filipino military pilots graduated: Class 49-A and 49-B each comprised of 27 pilots. Nearly all of them were converted to the Mustang, freeing the original prewar veterans to other positions in the PAF.

The original batch of P-51s was now a fraction of its original strength due to accidents and lack of repairs, and more were needed to go with the new pilots. The USA therfore delivered another 50 P-51 Mustangs in 1950, which had been set aside for the PAF, although some were diverted elsewhere due to the Korean War. According to some sources the Philippines volunteered a P-51 squadron for service in Korea, but the offer was not accepted, and Filipino forces in Korea remained ground troops.

The pilots were quickly installed in the fighter units, which now had between 10 and 15 pilots available at any time, each being given a personal aircraft, with more in reserve. The new pilots were put into action against the Huks, using the P-51's six .50 caliber machine guns, 250lb fragmentation bombs, 300lb GP bombs and rockets. Later in the campaign, napalm was used when authorized by headquarters.

The effectiveness of the Mustang probably remained limited. Brigadier-General Florendo F. Aquino recalls: "Most of the attacks were by two or four aircraft against suspected camps or troop concentrations. We didn't really see anything, and were seldom given the results of the attack." Another pilot adds: "There were lots of tree so we were given coordinates to spray bullets at, which we did without knowing what we were shooting at."

On one mission, Lt. Luis Diano had a close call: on hid first pass over the target, he tried releasing his bombs, but they remained attached to the aircraft. On the next pass he fired his rockets and then tried again to drop his bombs, expecting nothing to happen. To his horror, he felt the aircraft lurch up as the bombs dropped: he was far too low to drop bombs, and shrapnel from the explosions shredded the rear part of the Mustang. Diano nevertheless managed to return to base where his aircraft where written off as being beyond repair.

The Mustangs in the PAF were mostly used as fighter-bombers. Air-to-air combat training was also given but was not considered seriously for several reasons. First, there was no potential enemy, secondly, the PAF had no real fighter control organization. Even though a first radar was installed in Manilla in 1950, coverage was inadequate for fighter control.Thirdly, USAF units at Clark AFB were more capable of providing air defense to the Philippines, which was one of their attributions. Nevertheless, air combat training was done, often in cooperation with USAF units, or even units from Thailand or Taiwan. Since Basa was located between the USAF base of Clark, and the US navy base of Subic Bay, airspace was shared. Permanent instructions were given to US pilots not to dogfight with Filipino pilots unless official exercises were scheduled. On one occasion, it was Filipino pilot Lt. Antonio Dedal who jumped a US F8F for practice. The Bearcat simply went into a dive and easily escaped, greatly impressing the Filipino.

With the new pilots now available, the 8th FS was created and activated at Basa on August 1, 1951, commanded by Capt. Julian Yutuc. On September 22, the 5th FG was re-organized as the 5th Fighter Wing, to comply with USAF standards.

Through all of these administrative changes, things were still relaxed at Basa AB. Pilot Tony Dedal recalls:"We were like a club. There were no semblance of procedures. One night, as we were all snoring our heads off, somebody decided to fly at night and woke up the entire base. He could not sleep and had decided to take a night ride! Things like that were always happening at Basa."

The attrition rate was still very high, and even increased with the new generation of pilots. Indiscipline, machismo and poor flight skills caused many accidents. In 1950, Lt. José Dycayco crashed into the University of Manilla, after losing control of his aircraft while showing off to his friends. Another pilot lifted the tail of his P-51 on takeoff before airspeed was high enough for the rudder to have any effect. The engine torque sent the Mustang straight off the runway.

Mechanical problems still caused many accidents. Lt. Cesar Raval had to bail out of his P-51 at low altitude, when his engine failed on final approach to Fernando AB. His boots were jerked off his feet when he opened his parachute and he had to return to base barefoot. On his way back, he met a peasant carrying his boots. He failed to persuade the peasant to give him his boots back, and had to buy them back!

As most air forces operating the P-51, the PAF had problems with the retracting tail wheel and finally modified its aircraft to have the tailwheel remain in "down" position during flight.

Operation Four Roses

|

| Filipino Mustangs of the 8th FS in flight. Notice that the tailwheel has been locked in retracted position. The P-51's tailwheel often had problems, and after World War II several air forces modified their Mustangs so that the tailwheels would remain in retracted position. |

Operations against the Huks continued. A renewed offensive, named Operation Four Roses was launched im April 1952. Based on aerial photography and other information, the Mustangs flew 68 sorties against Huk camps in eastern Sierra Madre. Maybe the PAF P-51s were more effective this time, as an official history says they "wrought havoc and disaster on the fear-stricken Huks". By this time, two L-5s were acting as forward air controllers to assist the fighters, and this probably proved invaluable to the precision of the attacks.

Operations intensified during 1952 and 1953 and eventually subdued the Huks. Their main leader, Luis Taruc, surrended in 1954. In the following year, Huk activity died off only to reappear in the 1960s.

Although the Huk rebels were rapidly ending their guerrilla actions, a new rebel leader appeared in another province: Hadji Kamlon. A special task force, the JOTAF, was created to wage punitive operations.Detachments of the 6th FS and 7th FS were based on and off in Zamboanga in support for several years. As the major campaign of 1952-1953 was not giving good results against the Rebels, it was decided to increase air operations. Thus the Sulu Air Task Group (SATAG) was created on November 19, 1954 under the command of Maj. José Rancudo, CO of the 6th FS at the same time. The unit was made of 23 officers, 73 pilots, 8 Mustangs, 4 Consolidated Catalinas and 4 L-5s from various units. Two Sikorsky H-19 helicopters later complemented the unit.

The SATAG was responsible for close support to the JOTAF and also patrolled the sea lanes around Mindanao to cut off rebel supply lines. Starting in May 1955, pilots were given the permission to fire at suspected rebel targets without prior permission from the ground troops. Kamlon finally surrendered to governmental forces and the SATAG was disbanded in October 1955.

Col. Benito Ebuen, then commander of the PAF, sometimes flew combat missions in the Mindanao sector. Om one of these missions, he discovered a snake in his cockpit after takeoff. His return to base was swift!

As far as is known, no P-51s were ever lost to rebel fire, although many were hit by small-caliber rounds. On one mission, Maj. Rancudo returned to base with 27 bullet holes in his aircraft.

The Blue Diamonds aerobatics team

In 1951, 2nd Lt. Regino Masias was leading 2nd Lt. José Gonzales on a routine flight when he decided to take a sharp turn without warning him. To Masias' surprise, Gonzales stayed on his wing. He then tried a whole series of abrupt maneuvers, only to find that Gonzaled kept up with him every time. Another pilot, 2nd Lt. Oscar Alejandro spotted them and decided to join in.

Gonzales became very enthusiastic at the idea of an aerobatics team, and decided to realize the project. In 1952, some first attempts were refused official approval, but by early 1953, Gonzales was given the blessing of Maj. Rancudo, 6th FS's CO. The team was quickly formed with pilots from the 6th FS:

2nd Lt. José Gonzales Team leader

Maj. José L. Rancudo Alternate team leader

2nd Lt. Isidro B. Agunod Left wing

2nd Lt. Ricardo T. Sinson Right wing

2nd Lt. Pascual C. Servida Slot

2nd Lt. Cesar Raval Reserve

Once they started training, support for their team increased and they

were given permission to fly as an official PAF team by headquarters in

1953. The first public appearance was in November 1953 at an airshow during

Philippine Aviation Week at Manilla International Airport. Maj. Rancudo

was the team leader on this occasion. The day before, the team had decided

to appear under the name Blue Diamonds, a name inspired by the PAF insignia.

The performance was a great success.

Just before their appearance, a group of Taiwanese F-84G Thunderjets had arrived and made some impeccable formation turns and maneuvers before landing. Fearing the comparison, the Filipinos decided to start with a maneuver which had previously been judged too dangerous, with the team members alternatively rolling and making Immelman turns on takeoff. Gonzales in particular made a splendid performance and the direct violation of orders was overlooked by the 5th FW's commander, Col. Juliano.

The Blue Diamonds ran a few more public performances before the 6th FS converted to F-86s. Their last appearance was at the Philippine Aviation Week of December 1954.

In 1957, an attempt to recreate a Mustang aerobatics team with six aircraft of the 7th FS was led by Lt. Lino C. Adabia Jr., who crashed the day before the Philippine Aviation Week on a solo rehearsal flight. Once again, it was Maj. Gonzales who made an appearance with F-86F Sabres, although the pilots had less than fifty hours on the type.

Some of the ex-Blue Diamond members kept flying the Mustang after their conversion to the F-86 and became very proficient. In 1958, when only one Mustang squadron was left at Basa, an American instructor from Clark AFB visited the Filipino pilots. Gonzales, Singson and Servida decided to show him a few things, and took off with Mustangs. As soon as they were airborne, they rolled inverted and climbed.

José Gonzales was recognized as an unusually gifted pilot and had graduated from Class 51-A withe highest ratings. Tony Dedal recalls: "One guy I really respected was José Gonzales. He could fly the Mustang like nobody else. I flew wingman with him maybe twice in 1957, when he visited us at Nichols Fields as he was already at Clark flying F-86s. He would practice his proficiency in the Mustang, which was revealing to me with his masterly touch. His maneuvers were always tight and smooth. He would hang by the propeller and still pull enough Gs that you could not put him in your gunsights. It is difficult enough not to stall when following him. Some flight leaders I have flown with used more muscles on the controls but were in fact easier targets."

Farewell to props

With the end of the Korean War, the USAF resumed its deliveries of Mustang to PAF. Forty were delivered in 1953, 12 in the autumn of 1954 and a final 24 in 1955. This was the culminating point of the P-51's career in the PAF, with more pilots and aircraft available than ever before. At the 1956 Independence Day flypast, the 5th FW fielded 74 Mustangs.

However, the days of the Mustangs were counted. In July 1955, four veteran PAF pilots were sent to Japan to be checked out in T-33 jets, six of which were delivered to the PAF on August 5, 1955.

The Basa AB had to be improved to operate jet fighters, and the 5th FW was therefore temporarily relocated to Nichols Air Base in Manilla. The wing returned to Basa in 1957. During 1956, pilots of the 6th FS moved to Clark to train on F-86Fs. The first 30 Sabres were delivered in 1957 and in early 1958, the 6th FS became the first operational jet unit of the PAF. The 7th FS followed on the type starting in October 1958, returning to Basa with its F-86Fs in 1959. The 8th FS was the last to operate the P-51 and was later equipped with F-86D all-weather fighters.

There were still large numbers of P-51 serviceable and the PAF intended to keep them as advanced trainers. PAF Headquarters changed its mind when a pilot was killed in Mustang accident in June 1959. Obviously, the poor safety record of the PAF Mustangs was the reason: although no exact figures are available, probably as many as 30 pilots were killed in the P-51. Brigadier-General Casabar states "two squadrons worth of pilots killed." A final flypast was organized with four aircraft, and Lt. Romeo A Reinoso (Class 58) had the privilege of making the last Mustang lanfing in the PAF.

Most of the P-51s were scrapped, and none was returned to the USA, although a few were handed over to the CIA in 1958 for use in Indonesia, where they were flown by Filipino pilots. Three Mustangs at least were initially preserved : one each in Basa, Manilla and Zamboanga. The latter was still there in the 1970s but mysteriously dissapeared. It may have been sold or even smuggled abroad. The Mustang preserved at the PAF Museum in Manilla was exchanged in 1995 against a flyable Taiwanese F-5B Freedom Fighter. The sole remaining PAF Mustang at Basa survived the Mount Pinatubo eruption and is in rather good condition, though missing much of its interior.

Colours & Markings

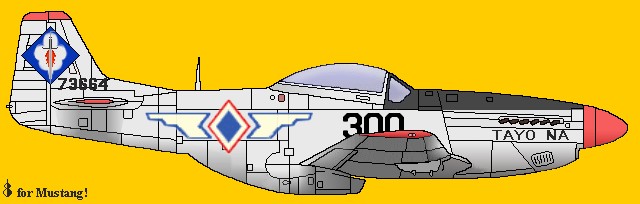

All PAF Mustangs retained the original natural metal/silver paint finish, with anti-glare panels in olive drab or black. National insignias were carried in four positions and the US serial number (or a shortened version of it) was retained on the fin. As a carry-over from the prewar days, the PAF P-51s carried tactical numbers on the fuselage, painted black. Each squadron was allocated a different series, and also different trim colours:

| HQ : 000-series registration - No trim colour 6th FS : 200-series registration - Blue 7th FS : 300-series registration - Red 8th FS : 400-series registration - Yellow |

For the first few years, the squadron colour was applied to the spinner and often the wing, stabilizer and fin tips. Around 1951, the spinner colour was extended in a point to the rear under the exhausts, and the squadron colour was outlined in black in every position. Finally, from 1954 or so, the squadron colour was usually reduced, appearing only on the rear part of the spinner. Some aircraft of SATAG were given blue and white stripes on their spinners to differentiate them from other units.

|

| The 'Shark of Zambales', belonging to PAF HQ. This aircraft was assigned to General B. N. Ebuen. A Mustang bearing these colours is preserved at Basa AB. Artwork ©Gaëtan Marie. |

Most Mustangs carried the 5th FW/Group insignia on the fin, and on a very few cases included the motto: 'Noli Mi Tangere' (Do not touch me).

|

| Another P-51D of the PhAF, called Tayo Na. Profile by Gaëtan Marie for Mustang! |

It was very common for PAF Mustangs to carry personal names, just as they did in the US. Initially the names where painted in white on the anti-glare panel. Later they often appeared under the exhaust and became more elaborate. In either case the names were applied on both sides. Cartoons and other figures were much less common, but not unheard of.

The Mustang of the Group/Wing CO often carried three diagonal red stripes around the fuselage or wings, while those of squadron COs carried two stripes. The aircraft of the Blue Diamonds did not carry any special markings.

Sources:

- Philippine Front line, P-51 Mustangs in the Philippine Air Force, Air Enthusiast magazine, May / June 1998, No.75, by Leif Hellström.

- Various personnal documents

This article was written by k51d. Version 1.2. Profiles by Gaëtan Marie. Any information, correction, data and especially photos concerning the Mustang in the Philippine Air Force is welcome.

Advertising |